Open Source Doesn’t Fail Because of Code!

Written by Ulises Gascón

Nov 24, 2025 — 8 min readOpen source rarely collapses in one dramatic moment. It erodes. Quietly. You notice it when releases stall, when issues stack up with no replies, when the same two names keep showing up on every commit log. That is what happened with Express and Lodash. Two of the most used JavaScript projects in the world, and long-standing pillars of the Node.js ecosystem. And for a period of time, both were much closer to irrelevance or accidental self destruction than most people realize.

This article builds on my talk What Comes After Chaos? Lessons from Reviving Express and reimagining Lodash. If you prefer video, you can watch it here:

Express and Lodash have touched an enormous portion of the modern web, appearing directly or indirectly in millions of Node.js applications and production websites. Not because they were trendy but because they were everywhere. Express quietly powers millions of servers, spanning dozens of repositories and tens of billions of yearly downloads. Lodash sits inside production applications, build tools and frameworks with billions of weekly installs and dependencies. This is not “popular project” territory. This is infrastructure.

And yet, scale does not protect you from decay. Sometimes it accelerates it.

When the Backbone Starts Cracking

Before the turnaround, Express had all the symptoms of a project that had grown larger than its own structure. Deep architectural decisions from the early Node.js era were becoming a performance and maintenance liability. Monkey patching, compatibility with Node.js versions nobody should still be running, and a test suite that was not stable enough to be trusted by Node’s own integration systems. Express 5 had been “almost ready” for close to a decade. Meanwhile, the effective bus factor in practice hovered around one, governance was informal at best, and the backlog of issues and pull requests kept growing.

Lodash had a different kind of challenge. They carried an extraordinary burden for years, and the problem was never their commitment, but the structure around them. Alongside this, hundreds of variant packages and a fragmented CI system made progress harder and riskier than anyone would want. The community was asking for Lodash 5, while the project was still trying to survive Lodash 4 without collapsing under its own operational weight.

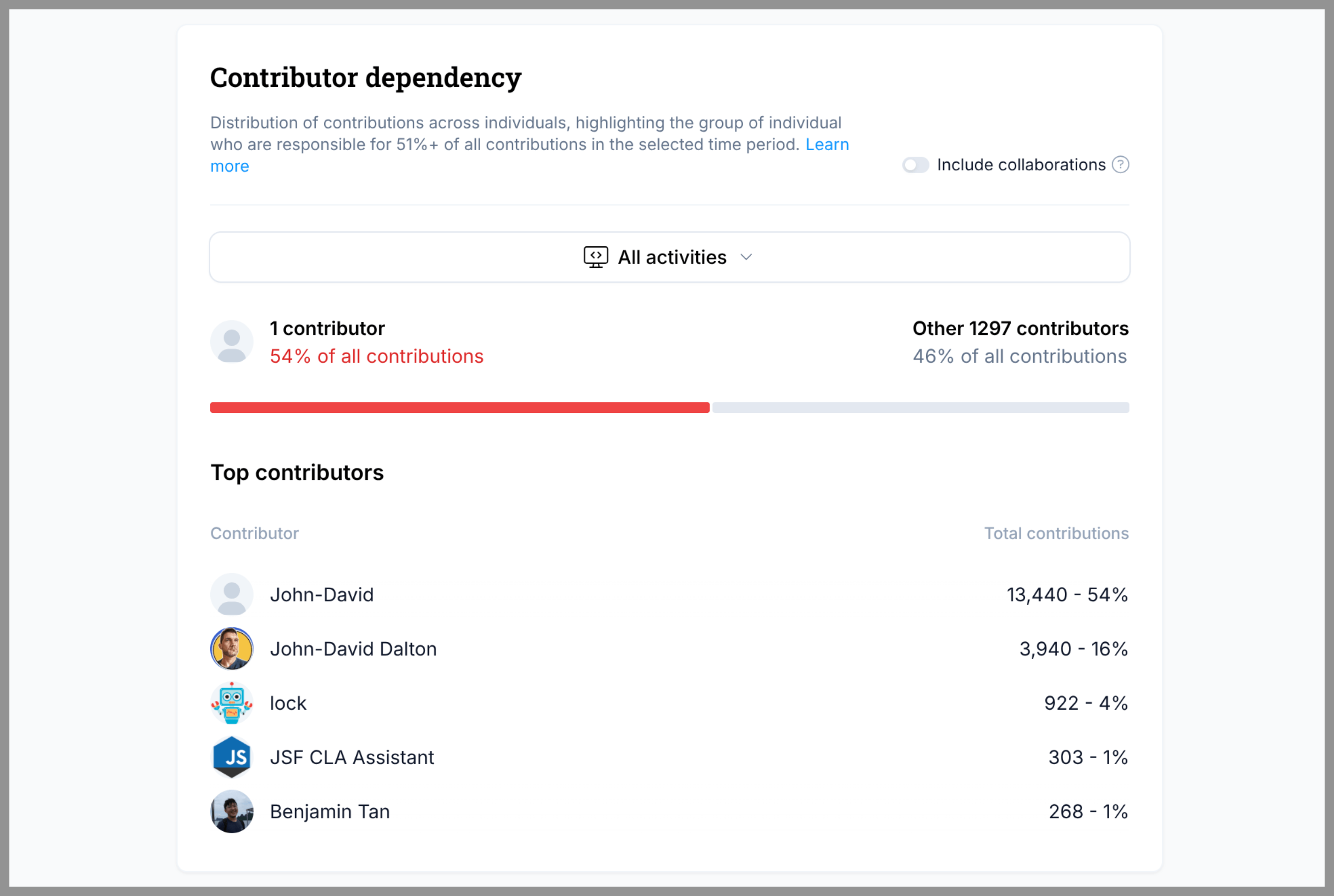

This is often the point where idealized views of open source meet reality. At this scale, burnout is not theoretical. It becomes visible and measurable in contribution patterns, response times, and maintainer availability. You could see it in contribution graphs, in response times, in the fact that two contributors carried more than half of Express for years. You could also see it in broader studies showing how close most maintainers are to walking away.

The important part is not that things were broken. It is that nobody had a sustainable way to fix them.

Chaos Is Organizational Before It Is Technical

People like to think that software collapses because of code. It does not. Code can be rewritten. Systems collapse when there is no structure around them to make decisions, handle conflict, and distribute power.

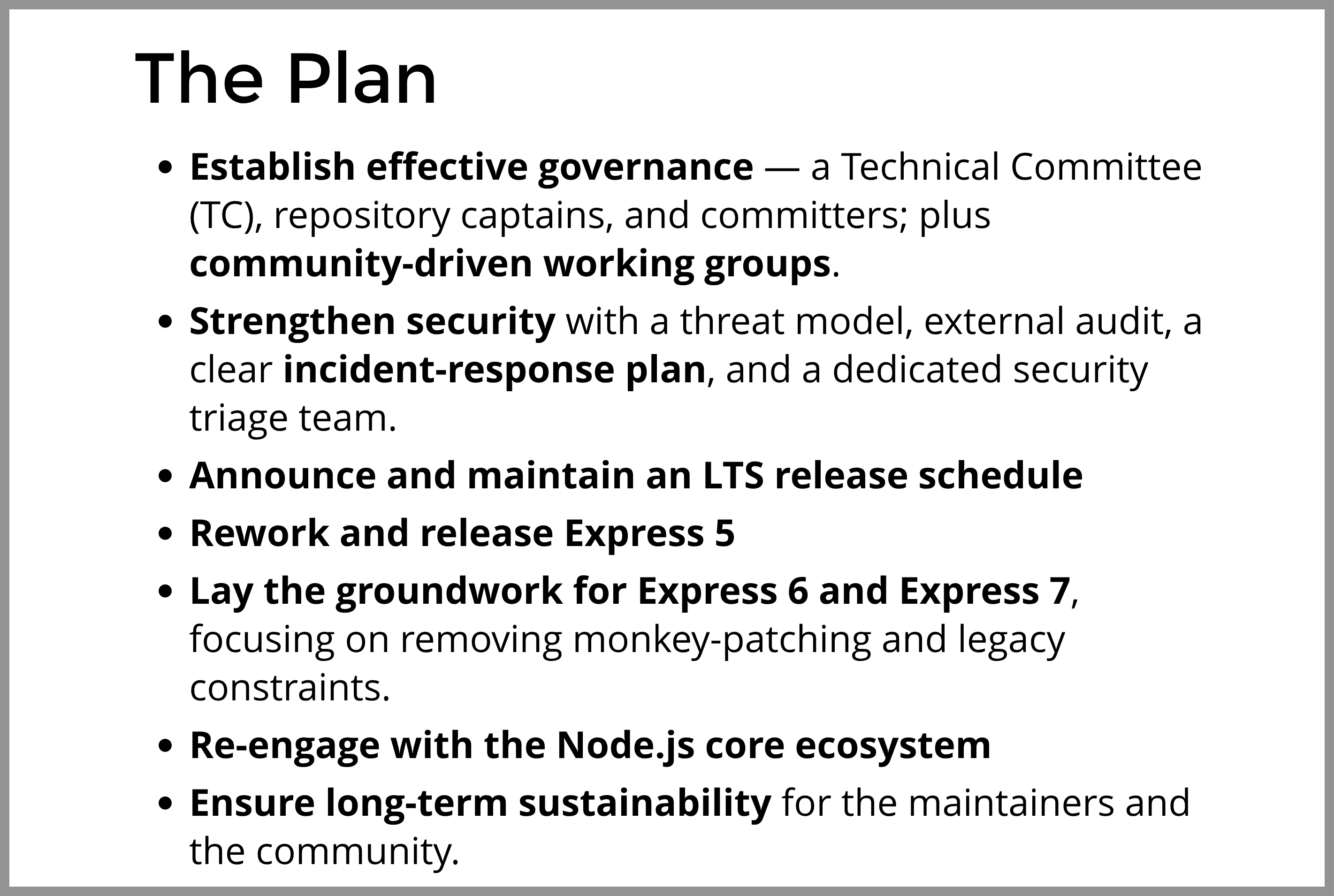

The first real change in Express was not a commit. It was governance. A proper Technical Committee. Defined roles like repository captains and committers. Transparent processes. Working groups with real responsibility instead of vague goodwill. Security was treated as a system, not a checklist: threat modeling, external audits, incident response playbooks, and a dedicated triage team. Releases were no longer wishful thinking. They were scheduled, maintained, and communicated.

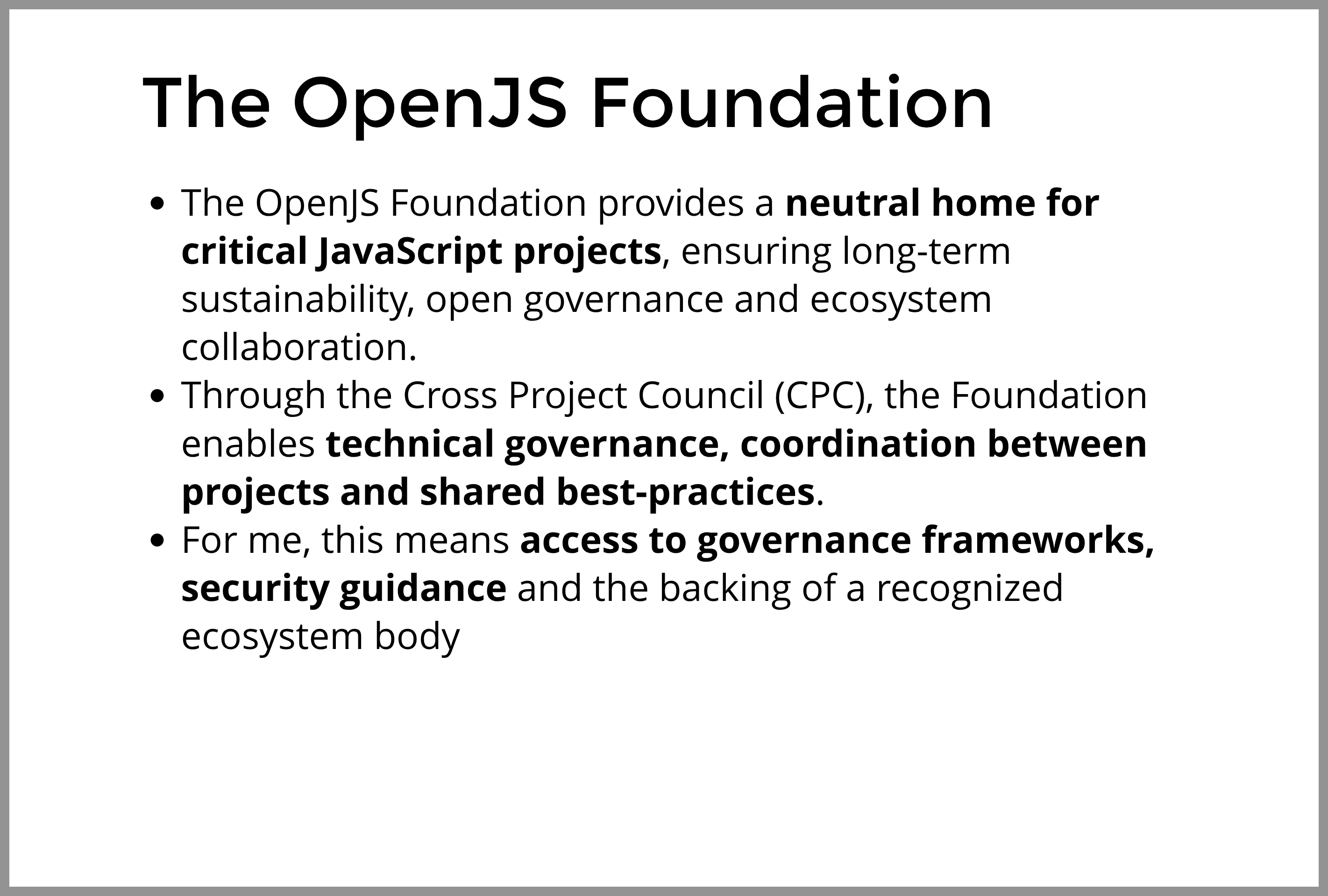

This mattered because it rebuilt something more important than code: trust. Not just from users but from contributors, companies and the wider ecosystem. Express was reintegrated into Node.js infrastructure testing, got Impact Project status under the OpenJS Foundation, and finally shipped Express 5 with a roadmap beyond it.

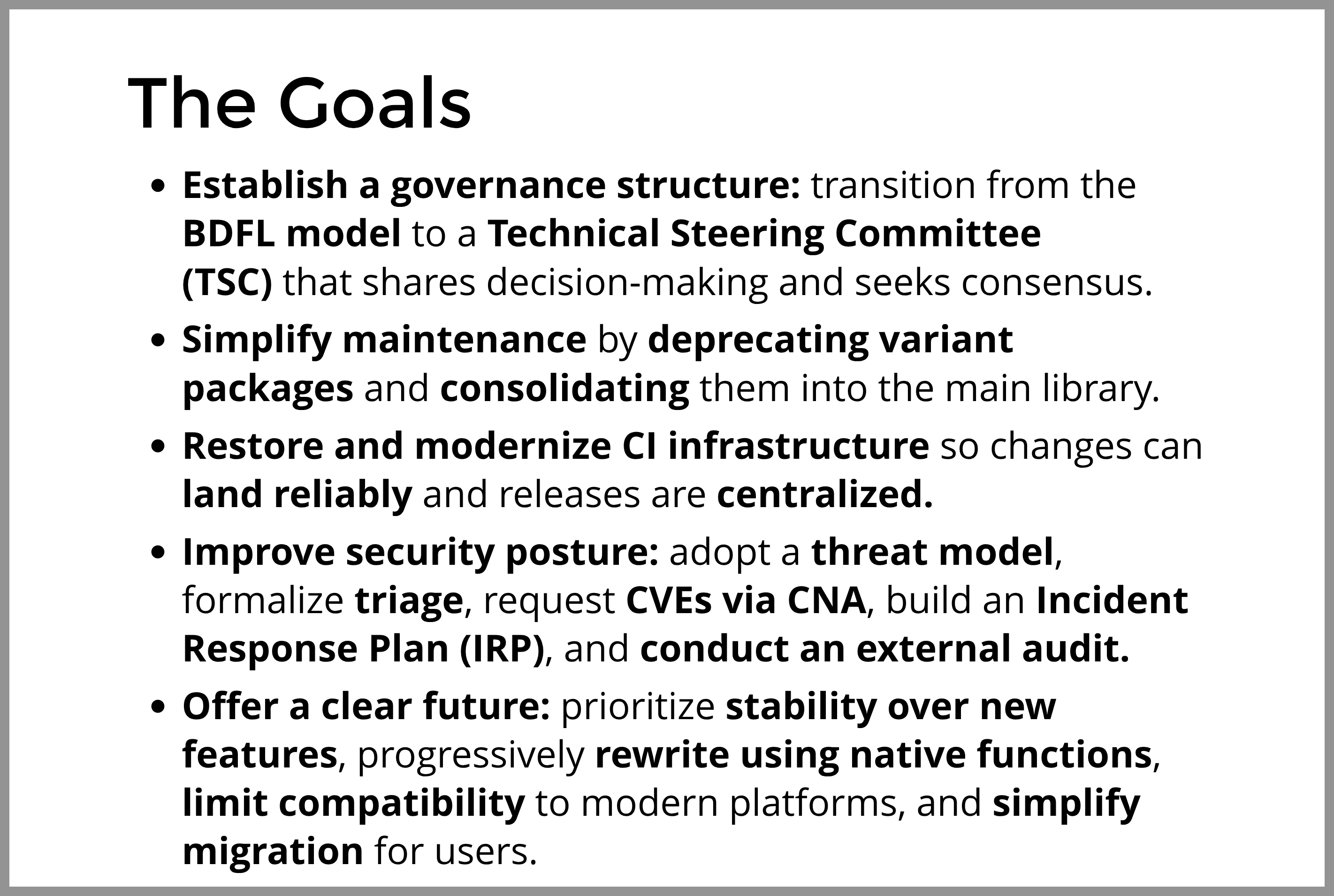

Lodash is following a similar path but with its own constraints and culture. Moving from a BDFL model to a Technical Steering Committee. Deprecating large parts of the variation ecosystem to regain control of complexity. Rebuilding CI so releases are no longer heroic efforts. Focusing on stability, security and progressive modernization, rather than prioritizing new features.

This is slower work. Less visible. Less exciting on social media. But this is what transformation looks like in mature infrastructure.

Not Everything That Looks Like Drama Is One

When projects as big as Express or Lodash make changes, the internet often frames it as a crisis or a scandal. Spam PR incidents. “Is this project dead?” blog posts. Threads about abandoning libraries for “lighter” alternatives. Most of that noise misses the point. Mature ecosystems will always generate friction because they have gravity. But not every moment of tension is a failure. Sometimes it is just the cost of moving from informal to intentional.

What matters is not whether conflict exists. It is whether the project has the structures to handle it without burning people out.

What Actually Survives After Chaos

Express today is not just a framework. It is an organization. Lodash is no longer just a utility library. It is a project learning how to scale its governance as much as its code. The invisible work behind that shift is often ignored: mentoring new maintainers, distributing decision making, documenting processes, creating safe spaces for disagreement, and making sure security and sustainability are treated as first-class concerns, not afterthoughts.

Open source does not survive on pull requests alone. It survives on structure, on shared ownership, and on the uncomfortable decision to stop being heroic and start being boring.

And that is what comes after chaos. Not perfection. Not a happy ending. Just transformation. Slow, deliberate, sometimes frustrating, and absolutely necessary. If you have ever typed npm install express or npm install lodash, you have already been part of that story whether you knew it or not.

It’s also worth saying the uncomfortable part out loud. We didn’t fix this because a magic pile of money appeared. Support does matter, and initiatives like the Sovereign Tech Fund have made a real difference in making this work possible. But funding alone does not solve structural problems. In most cases, the resources are still not enough. Structure, governance and shared ownership carried more weight than budget ever did. And even when projects are “rescued” and celebrated, their long-term sustainability is still fragile. Recovery is a phase, not a conclusion. It needs constant maintenance.

What Comes After Chaos… it’s just transformation.